Scaling Climate Smart Agriculture: what are we missing?

Scaling Climate Smart Agriculture: what are we missing?

AUTHOR: Tomaso Ceccarelli

PUBLISH DATE: 09 SEPTEMBER 2024

This blog article is a follow-up to the side event “Climate Smart Solutions: scaling pathways” in the Africa Food Systems Forum's 2024, Kigali, and in support of the eConversation on the same themes.

In the face of climate change, agriculture must evolve (quickly) to become more resilient, adaptive, and sustainable. This is where Climate-Smart Agriculture (CSA) enters the conversation. However, while the concept of CSA is frequently invoked, its definition and implementation often remain elusive. To effectively address barriers to adoption, and chart clear pathways for scaling I believe that we need to dissect and understand its different dimensions first.

What is Climate Smart Agriculture, exactly?

First, we need to define what is CSA more clearly because the term may cause ambiguity. If we do not know more precisely what we are referring to, we cannot discuss the factors that determine scaling, and more specifically adoption or rejection by users.

Climate SmartAgriculture (CSA) was first defined in a 2010 report by The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations. FAO also indicates CSA as ‘Agriculture that sustainably increases productivity, resilience (adaptation), reduces/removes GHGs (mitigation), and enhances achievement of national food security and development goals’. It recommends the approach is implemented through five action points: ‘Expanding the evidence base for CSA, supporting enabling policy frameworks, strengthening national and local institutions, enhancing funding, and financing options, and implementing CSA practices at field level’.

The World Bank (WB) indicates that CSA should be able ‘to promote sustainable development and end food insecurity while addressing climate change issues’ through ‘a set of agricultural practices and technologies tailored to specific agro-ecological conditions and socio-economic context including the adoption of climate-resilient crop varieties, conservation agriculture techniques, agroforestry, precision farming, water management strategies, and improved livestock management’.

Precision agriculture and livestock on the one hand and on the other agro-ecology, organic farming, conservation, and regenerative agriculture, as well as other forms of sustainable agriculture are other approaches to farming, to some extent overlapping with CSA although, at least at present, having less potential for deployment in LMICs.

If climate and agriculture are more or less clear concepts (but as we will see, they also deserve some discussion) what is a bit fuzzier is the aspect of smartness.

Let’s consider the three terms one by one.

Climate

This connotates the main scope of CSA. The digital solutions (With a digital solution we mean one or more digital technologies (e.g. satellites, Internet of Things (IoT) devices, weather forecasting) used for a specific product or service, addressing a specific use case (e.g. yield prediction, agro-meteo advisory, irrigation management) offered, however, can be very diverse when referring to long-term (climate) or short term (weather) processes, and currently are mostly related to the latter.

Smart

The WB also implies that CSA ‘systematically considers the synergies and tradeoffs that exist between productivity, adaptation, and mitigation’ revealing opportunities for co-benefits and potential ‘triple-wins’.

The task is challenging, and the ambition to achieve these ‘triple-wins’ is likely the explanation for pursuing ‘smartness’.

In a 2022 study as part of the Digital Agri Hub project, GSMA highlighted that Smart Farming is about solutions for the automation of decision-making at the farm level, through digitalization. This involves ‘the use of on-farm and remote sensors to generate and transmit data about a specific crop, animal or practice to enable the mechanization and automation of on-farm practices and achieve more efficient, high-quality and sustainable production of agricultural goods’.

Agriculture

The term is clear but the question here is, adoption of what precisely?

The GSMA study has identified concretely three use cases: smart crop management, smart livestock management and mechanization access services. There is clearly an integration or at least a synergy, therefore, between agricultural technologies (Agtech) and digital components.

The spectrum of the solutions proposed is very wide, being applied at various stages of the agricultural cycle, in the case of cropping from land preparation to crop distribution.

This means that the very objectives and, therefore, the nature of the CSA solutions is broad and difficult to grasp: CSA solutions may consist of a GPS on a tractor, a soil moisture IoT kit, a heat-resistant wheat variety, a heavily automatized cold storage facility, a paddock management automated system, agri-insurance products or a weather forecasting service. At the same time local, adapted, and low-tech solutions may well be ‘climate-smart’.

The role of Digital Climate Advisory Services (DCAS)

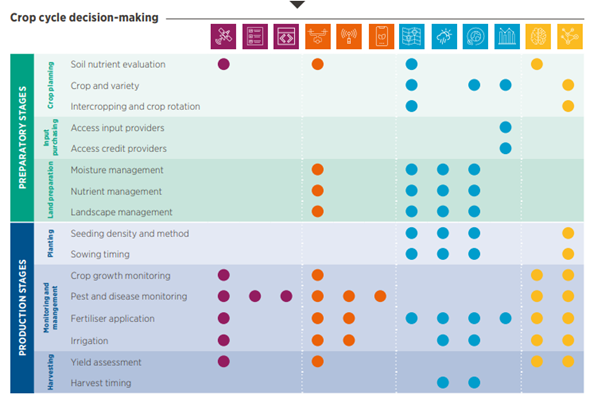

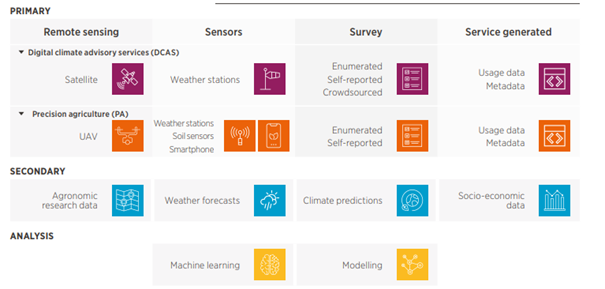

Digital Climate Advisory Services (DCAS) are at the core of what CSA solutions deliver. In a study in 2018, the WB classified different types of CSA to conclude that ‘While CSA is diverse, just five technology clusters: water management, crop tolerance to stress, intercropping, organic inputs, and conservation agriculture, account for almost 50% of all CSA technologies’. In another study by GSMA in 2022 technologies were connected to solutions and solutions in turn, related to the crop-cycle and specific decision-making processes, as shown in the figure below:

Figure 1: CSA solutions and crop-cycle decision-making. Source GSMA, 2022.

Figure 2: Data sources and analysis approach. DDAS-informed decision-making during the cropping cycle. Source GSMA, 2022.

In the ‘State of the Digital Agriculture Sector’ study of 2023’ what are defined as ‘Climate Smart Digitalisation of Agriculture (D4AG) solutions, are further described in relation to their contribution to either climate change mitigation or adaptation.

Adoption of CSA solutions

The question of adoption by whom is also important: by small-scale producers specifically? By all farmers? It makes a lot of a difference since the former may well have little endowments in terms of land, capital, skills, and therefore margins for risk-taking.

The specific geographic and socio-cultural settings are also important as small-scale producers and other actors may have different adoption potentials depending on agroecological and value chain circumstances as well as their general enabling (or often disabling) context.

A prerequisite to assess adoption and potential for scaling, therefore, seems to be a minimum of knowledge and recognition of specific drivers and barriers. As we have seen above, to be meaningful, this assessment should be articulated by type of solution, farmer (or other stakeholders), agroecology and geography in general.

That being said, the cited WB study identified the lack of training and information as the single largest barrier to CSA adoption across all regions.

A weak enabling environment —including lack of unfavourable policies, lack of access to input and output markets and inefficient risk management systems- as well as insufficient economic resources were identified as other barriers to CSA adoption.

The cited GSMA 2022 publication indicated the following barriers to adoption:

- Limited digital and technical literacy (back to the training point above)

- High cost of connectivity and ongoing services

- Limited network reach in rural areas.

Other barriers usually cited include lack of knowledge and awareness, limited access to physical resources (e.g. land, water, seed, plant protection means, and also information), financial constraints, insufficient government policies or support systems, and cultural and social factors.

In the ‘State of the Digital Agriculture Sector’ study, a number of challenges were identified, often overlapping with the ones mentioned in the other studies:

Lack of Agency: Smallholder farmers are often unable to act on the recommendations provided through digital advisories or other guidance systems. In the context of digital agriculture, the implication is that advisories must be mindful of the real constraints farmers face.

Unproven Business Models: DCAS solution providers have largely struggled to monetize their offerings. This is particularly challenging in contexts where farmers are used to receiving subsidized advisory services for free or at a low cost. This was also one of the main conclusions in the “Digitalisation of African Agriculture Report 2018-2019” by CTA and Dalberg.

Furthermore, demonstrating the value proposition of these services to farmers and getting them to pay for premium features can be difficult, especially when the benefits of adopting climate-smart practices may take time to materialize. The bundling of more services is indicated as a way forward in this sense although it is noted that ‘subsided advisory-only services built in collaboration with donors and government extension agents remain a crucial tool for serving marginalized farmer groups in many LMICs’.

Also noted in the sector study is that for climate-smart advisory services to be effective, there needs to be a strong collaboration between climate change experts, and D4Ag stakeholders, who understand the practical realities of farming and agricultural markets. This is despite, in many cases, an observed disconnect between these two groups which can lead to a lack of practical and actionable advice for farmers. Therefore, the co-design of solutions between knowledge providers, developers, and users (or ‘honest brokers’ of their needs: farmers are usually busy people…) appears to be also crucial.

But there are other basic reasons, often neglected, which refer to the contents themselves of the CSA solutions: relevance (fit for purposeness), trustworthiness, and evidence of cost reductions in farming through improved efficiency and resource management. In other words, a lack of quality and granular data, not sufficiently differentiated to reflect the diverse conditions and needs of different farms or regions” remains an important barrier despite big advancements e.g. through remote sensing and other ‘big data’ on the data side, and machine learning, etc. on the data analytics.

The studies cited indicate that addressing these barriers can be done through education, financial support, and policy frameworks that can help promote the adoption of Climate Smart Agriculture.

Which of these means is more effective?

Evidence on the adoption of CSA

Do we have sufficient evidence on the adoption and ultimately the factors behind the scaling of CSA solutions? Very limited, it seems.

In the cited sector study an attempt was made, namely for three types of solutions: Digitally Enabled advisory for whom adoption is said to be medium-high, Digitally Enabled Microinsurance, with a medium-low level of adoption, and Digital Market Linkages & Access (MRV), which are said to have a low-level adoption.

However, in the study above, the impact analysis consists of a review of other publications, including the ones cited by GSMA, and not on ad-hoc surveys. Can we conclude that the impact of CSA solutions represents an important gap in our knowledge?

Call for action

From this picture, which likely omits other relevant studies and experiences in the field (Which we ask our attentive community of readers to point out to us), several priorities emerge in our view, that need a call for action:

A taxonomy of CSA solutions expanding/updating what was initiated by the WB and GSMA, as a condition for properly assessing drivers and barriers, hence adoption potential

An assessment framework to be articulated also per category of CSA solutions (as discussed earlier), type of farmer or other relevant stakeholders, type of agro-ecological and policy-institutional conditions

This is a precondition for much-needed impact studies again articulated as above, as a way to create further evidence on the adoption and scaling pathways.

The authors would like to acknowledge funding for project KB-35-104-002 Organising active dialogues from the Wageningen University & Research "Food and Water Security programme" which is supported by the Dutch Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries, Food Security and Nature.